Barry Meier’s “Spooked”

By Glenn R. Simpson and Peter Fritsch

In a new book, former New York Times reporter Barry Meier denounces his fellow journalists with great sanctimony for considering information from private research companies like ours, Fusion GPS. This past Sunday, The Times published an adaptation of the book as a news story on the cover of the Business section, largely focused on attacking our research into the Trump campaign’s ties to Russia during the 2016 election. It did so without disclosing several awkward facts.

The first is that Meier’s wife Ellen Pollock edits the Business section where Meier’s piece was given front page treatment. She has been promoting her husband’s book and presumably has a financial interest in its success. Readers should have been informed of that fact.

Second, the Times never sought our comment for the story. We declined to help Meier with his book — we wrote our own, that covered much of the same ground, in 2019. However, we should have been contacted before a critical news story ran in the Times, as is standard practice for any reputable publication.

But by far the most salient fact that Meier omits in his book and news story is that he himself repeatedly contacted us for help on Times stories before, during and after the 2016 election. We would generally consider our correspondence with a journalist to be confidential, but Meier’s extraordinary hypocrisy warrants an exception.

Meier admits his dealings with our firm, sort of, in a parenthetical on the penultimate page of his book, though nowhere in the Times: “(While I was at The New York Times, I spoke with Glenn Simpson on several occasions, though I don’t recall writing anything based on our discussions.)”

Well, we do.

Manafort Documents — “Could you kindly send it to me or point me in the right direction”

In August 2016, Meier wanted our help with one of the Times’ most important stories on the Trump Russia saga: an exposé of illicit payments that former Trump campaign chairman Paul Manafort received for his work in Ukraine. That story cited public records that we directed him to — a key element of the story and its ultimate conclusions.

As we recounted in our book, Crime in Progress, we had investigated Manafort’s political consulting work with the pro-Russia Ukrainian government as Wall Street Journal reporters in the mid-2000s. When Manafort joined the Trump campaign in early 2016, we immediately knew he represented a bridge to Russia, and dug into public records around the world. Our most important finding: Virginia court records that showed Manafort was deeply indebted to a pro-Putin oligarch named Oleg Deripaska.

By the time of the Democratic National Convention in July, we had been researching Trump for some 10 months — work that began for Republicans and was later continued for Democrats. On July 25, 2016, we met on the sidelines of the convention in Philadelphia with two of the Times’ top editors, Dean Baquet and Matt Purdy, to share information about our Trump-Russia research.

Among the topics we discussed was Paul Manafort’s prior work for Ukrainians backed by Putin. The next day, at Purdy’s request, we sent the Times a pile of public record documents that supported a conclusion that Manafort was in a compromised position in relation to Moscow, including records that showed he owed millions of dollars to Deripaska.

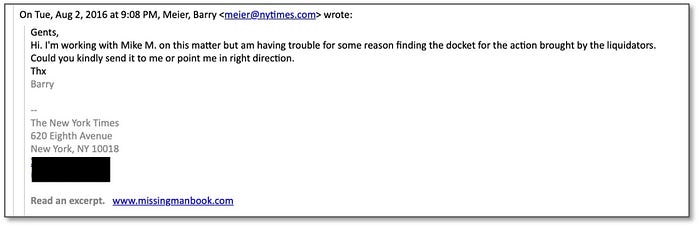

Purdy connected us with two of his top reporters. Barry Meier was also assigned to the story. He was having a hard time locating the Virginia court records we’d mentioned to Purdy and Baquet and reached out to Simpson and a colleague for help.

Fusion helped Meier find the records, and they featured prominently in the Times story published two weeks later, proving a vital link connecting Manafort and Deripaska:

“Kindly Send Me What You Have”

The Manafort story had a dramatic effect. It led to his dismissal from the Trump campaign and broader scrutiny of the campaign’s Russia ties. It was also emblematic of how we have worked with reporters at the Times and elsewhere. We don’t claim credit for this Times scoop, we merely had a piece of the puzzle to add, presumably like others who spoke to them confidentially.

There is nothing exotic or sinister about this type of shoe-leather work, as the episode shows, and Meier knows that better than most. Still, he chose to mischaracterize us as spies and media manipulators. Indeed, for all Meier’s claims that we “pushed” and “peddled” information, he neglects to mention that it was often he and his Times colleagues calling us, not the other way around.

Our help on the Manafort story evidently encouraged Meier to continue seeking our input over the following years, on stories about Trump-Russia and other matters. A few examples:

How strange then, that the same Barry Meier would be so upset to learn that reporters often speak to sources on background, writing in the Times:

“Reporters and private investigators long have had a symbiotic relationship that is hidden from the public. Hired spies feed journalists story tips or documents and use reporters to plant stories benefiting a client without leaving their fingerprints behind. The information they peddle is often sensational. It can also be impossible to verify or be untrue.”

Meier’s attack on us — and on reporters who consider information from private researchers — is disingenuous, hypocritical and profoundly ironic. So is the Times’ decision to publish it prominently and without disclosures about Meier’s wife and his communications with us. As both well know, reporters routinely seek help from a range of knowledgeable sources — lawyers, prosecutors, public officials, politicians, activists and yes, opposition researchers — all of whom have different agendas. Journalists are quite capable of considering a source’s motives and reliability while evaluating such information. They do it every day.

Rather than wrestle with this honestly, Meier draws upon a surfeit of propaganda about us produced over the last five years by Republicans, fake news sites funded by right-wing plutocrats, and well-known agents of Russia. Having found virtually no new facts, Meier recycles the sinister mood music, handwaving and innuendo used by Trump’s worst apologists to imply that there is something improper about us talking to journalists.

In fact, as the Manafort story shows, the strength of our research — and its foundation in public record documents that are easily verified — explains why journalists around the world often choose to compare notes with us about their own investigations.

As for the Steele Dossier, a small sliver of the 2016 research on Trump, we wrote an entire book to help explain its origins and context. Please read it. We are proud that we helped uncover — in real time — Russian interference in the 2016 election, including a mountain of public records showing that Trump had been deeply compromised by Russian money flowing through his businesses. Since then, multiple government investigations and prosecutions have validated our work.

Meier’s attack on us — and on reporters who consider information from private researchers — is disingenuous, hypocritical and profoundly ironic

Meier insinuates the whole thing was a bum steer. How inconvenient for him, then, that just ahead of his book’s publication, the US Treasury declared that Manafort, while Trump’s campaign chairman, handed sensitive internal polling data on swing states to a “known Russian Intelligence Services agent.” Collusion anyone?

No one who knows us and our work recognizes the grotesque caricature Meier has painted of our company. No one here is a “private spy” or an “operative,” which in Meier’s view seems to be anyone working outside of a newsroom. Our work has little in common with those he lumps us in with in his book.

But there’s a broader issue at stake. By implicitly backing the lies spun by Trump, the Kremlin and their allies, the Times is helping muddy the waters about what happened in 2016. Their allies successfully created a fog of misinformation around the Trump-Russia investigation. Meier and the Times should not be contributing to it.

Theranos

Meier seeks to tarnish us, too, by recounting an episode from our work six years ago for the now-disgraced blood testing company, Theranos. When we were hired in spring 2015 by the law firm Boies Schiller on behalf of Theranos, the company was riding high, with its founder on the cover of the Times’ style magazine and many others.

As we already described in our book, they hired us to investigate whether its rivals were overbilling Medicare, and Peter Fritsch originally reached out to John Carreyrou, a former colleague from The Wall Street Journal, to share those findings. Later, when it became clear that Carreyrou was focused on Theranos, Fritsch immediately disclosed to him our work for the company and added:

“I very strongly encouraged [Theranos] to be open and fulsome in giving you access and dealing with your questions…said that it was in their interest because the current canon of coverage of them (imo) borders on hagiography and they need to starting dealing with the serious media fluent in things. . . . Anyway, wanted you to know [that Fusion was working for Theranos] and if that a) means you don’t wanna talk further, cool and b), if you do, cool. . . .”

In his book and the Times excerpt, however, Meier concocts a more sinister version of these facts, wrongly suggesting we were hired to talk Carreyrou out of his story: “Once Theranos caught wind of Mr. Carreyrou’s interest, its lawyers hired Fusion GPS.” That is flat wrong, and the Times should correct it.

There are entire firms filled with former journalists that specialize in “crisis PR.” That’s not what we do, and it isn’t what we did for Theranos. Instead, we mainly locate and analyze public records. Part of that work included a number of requests for Carreyrou’s contacts with government officials under the Freedom of Information Act, to see what the FDA was disclosing to reporters.

Meier portrays this public records request as an act of espionage. Please. Open-records laws are not a tool only journalists are entitled to use. Many reporters routinely ask for logs of pending requests by others to find out what is being released by the government and, yes, to see what the competition is getting.

The private research industry and its relationships with journalists in an era of declining media resources is a topic worthy of a nuanced, book-length treatment. Spooked is not that book. Meanwhile, we still desperately need smart and honest journalists to dig deep about what occurred during the Trump era. When they do, they will consult a range of knowledgeable sources, quite possibly including us.

Just as Barry Meier did.

The authors are co-founders of Fusion GPS.